Neal Grantham

Who Reviews the Pitchfork Reviewers?

Pitchfork is the largest indie music site on the Internet (in the English-speaking world, at least), updating its pages daily with the latest indie music rumblings, interviews with budding artists, sneak previews of new albums and artist collaborations, and, most notably, a suite of music reviews by dedicated music critics forming Pitchfork’s staff. I follow Pitchfork’s album reviews religiously and I am not alone in feeling that their ‘Best New Music’ category routinely captures the best that modern music has to offer.

Since its creation in 1999, Pitchfork has gained quite the following among music fanatics and its widely-read album reviews can have a demonstrable impact on an album’s success. Indeed, Pitchfork is credited with propelling Arcade Fire into the limelight after bestowing a glowing 9.7 ‘Best New Music’ review on their 2004 release Funeral. Conversely, they are responsible for striking a devastating blow to Travis Morrison’s solo career after his 2004 release Travistan received a controversial 0.0. This make-or-break phenomenon has appropriately been dubbed The Pitchfork Effect.

Simply put, an album’s commercial fate can rest squarely in the hands of the Pitchfork staff member responsible for its review. But what goes into a review? Are staff members consistent in their reviewing behavior? Do biases exist? If so, what kinds? In the following post, I analyze Pitchfork’s data in an attempt to answer these questions. After all, who reviews the reviewers?

All the reviews that are fit to parse

To download Pitchfork’s full catalogue of 16,080 album reviews I wrote a python script that scrapes and parses Pitchfork’s pages using urllib2 and BeautifulSoup, respectively, and saves the data into a SQLite database via sqlite3. I then load these data into R and analyze them using a handful of packages including dplyr, magrittr, and ggplot2. For more details on the mechanics behind the data collection and analysis1, please visit my pitchfork-reviews GitHub repository.

These album reviews include both new releases as well as reissues. Reissues are typically multi-CD re-releases from already successful artists, often with extra artwork, remastered audio, remixes, or bonus tracks added to sweaten the deal. For example, see David Bowie’s recent ‘Nothing Has Changed’ Deluxe Edition or the highly anticipated remastered My Bloody Valentine album set. In my analysis of album scores by reviewer, I am interested in initial album releases rather than reissued content from well-established artists.

I therefore attempt to remove reissues from my data set, but this is not straightforward because albums are not explicitly labeled as “new” or “reissued.” I can, however, confidently remove the most successful reissues designated as ‘Best New Reissue’ by Pitchfork. Eliminating these 235 reissues leaves a remaining 15845 reviews comprised of all initial album releases as well as, unfortunately, reissues not distinguished by ‘Best New Reissue.’ This is not ideal, and the following analyses ought to be given a certain degree of wiggle room as a result, but I imagine the effect of these lingering reissues is relatively negligible. It is my personal experience that a large proportion of Pitchfork reviews pertain to initial album releases over reissues.

A brief history of album scores

Pitchfork published its first-ever album review on January 05, 1999. 16 years later, Pitchfork boasts reviews of 16,080 total albums from 7,502 distinct artists and 3,845 music labels. For the following analyses, we consider a smaller subset of these reviews (15,845) after removing 235 ‘Best New Reissue’ albums.

Reviews consist of a brief discussion of an album’s musical content (e.g., does the album succeed in breaking new ground, where does it fall short, what are the must-listen-to tracks, etc.) and a numeric score assigned to the album ranging from 0.0 to 10.0 in incremements of 0.1. The higher the score, the higher the perceived quality of the album. Most often, an album’s review is conducted by a single member of Pitchfork’s staff.

We can numerically summarize Pitchfork’s history of album scores.

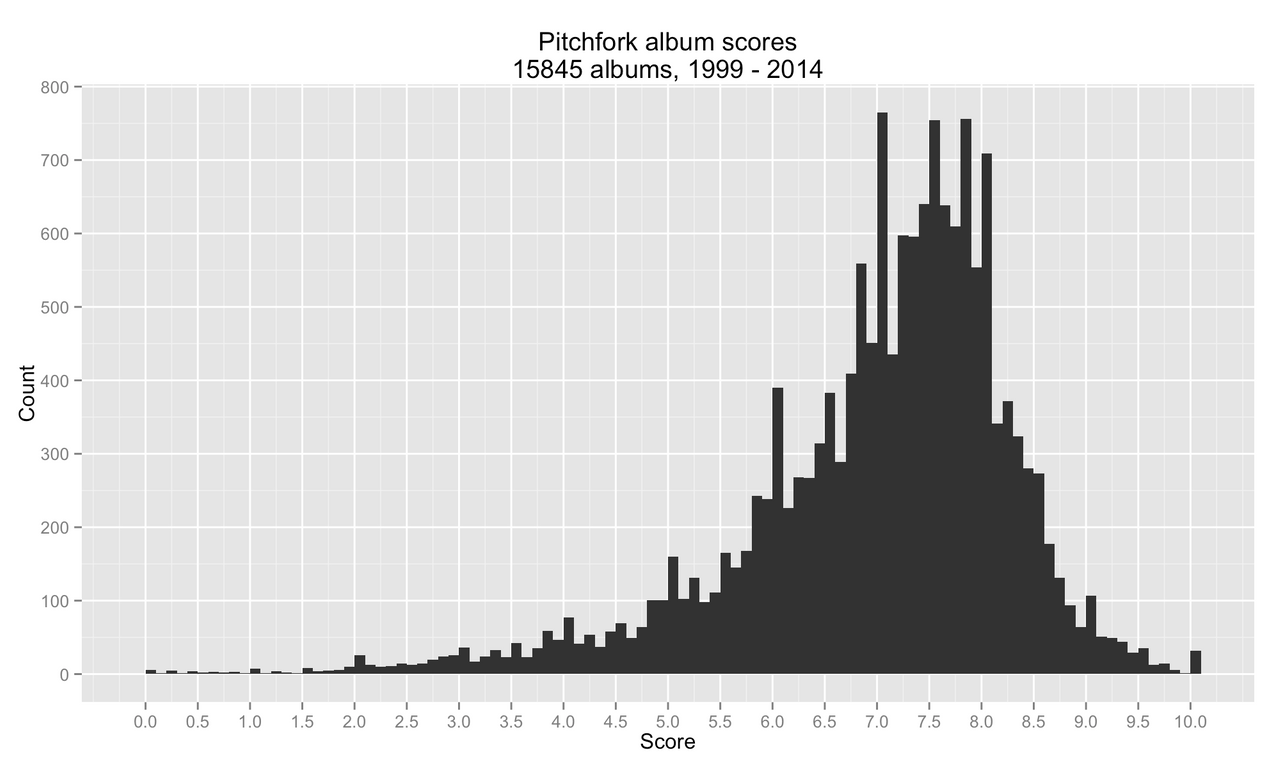

## Min. 1st Qu. Median Mean 3rd Qu. Max.

## 0.00 6.40 7.20 6.95 7.80 10.00

One quarter of all reviews earn scores that fall at or below 6.4 and half of all scores land in a narrow interval from 6.4 to 7.8. The remaining quarter albums are fortunate to earn 7.8 or above. On average, the mean score is 6.95 and the median score is 7.2. A visual depiction paints a much richer picture of scoring history.

The five most common scores are 7, 7.8, 7.5, 8, 7.4. There is a clear preference for whole number scores (5.0, 6.0, 7.0, 8.0) as well as half number scores (5.5, 6.5, 7.5). Among highly acclaimed albums, 32 have received a perfect score of 10.0 and 34 have come very close (9.6 to 9.9).

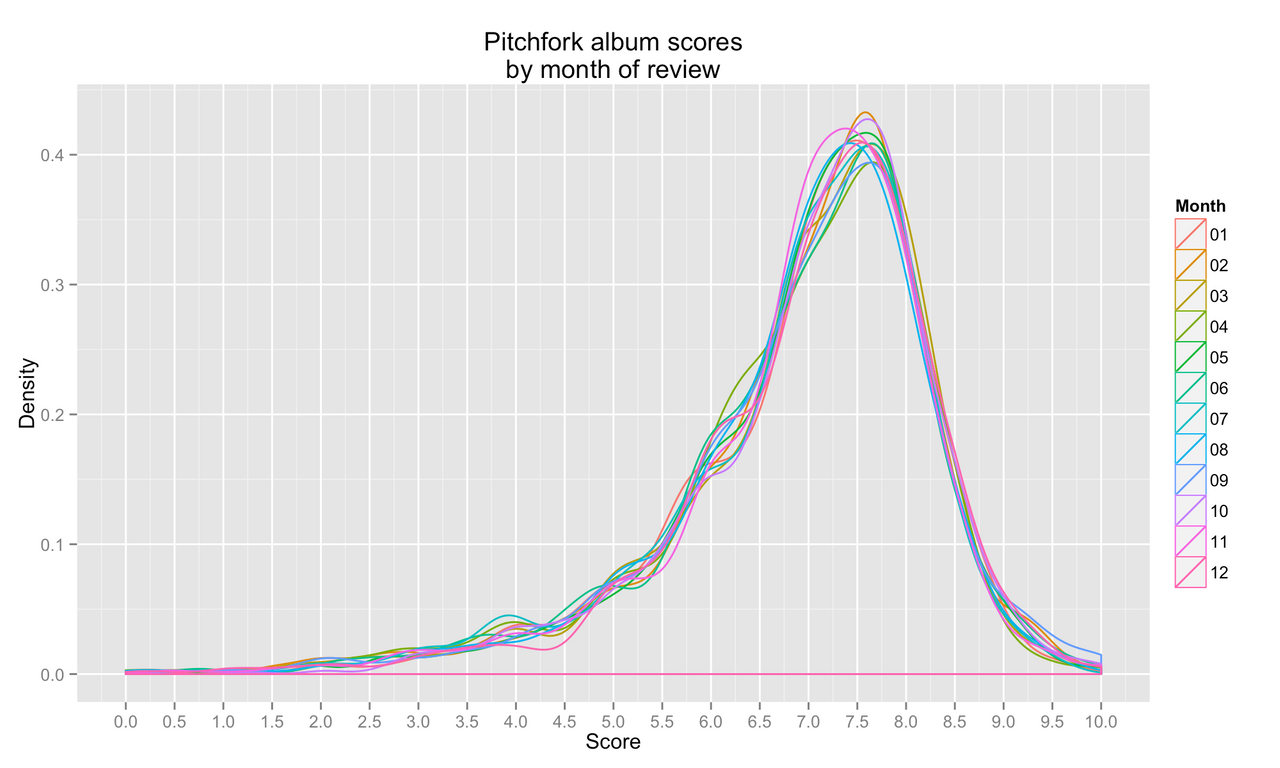

By month

Do scores depend on the month in which they’re reviewed?

It doesn’t seem so, there is no discernable difference in score distribution by month.

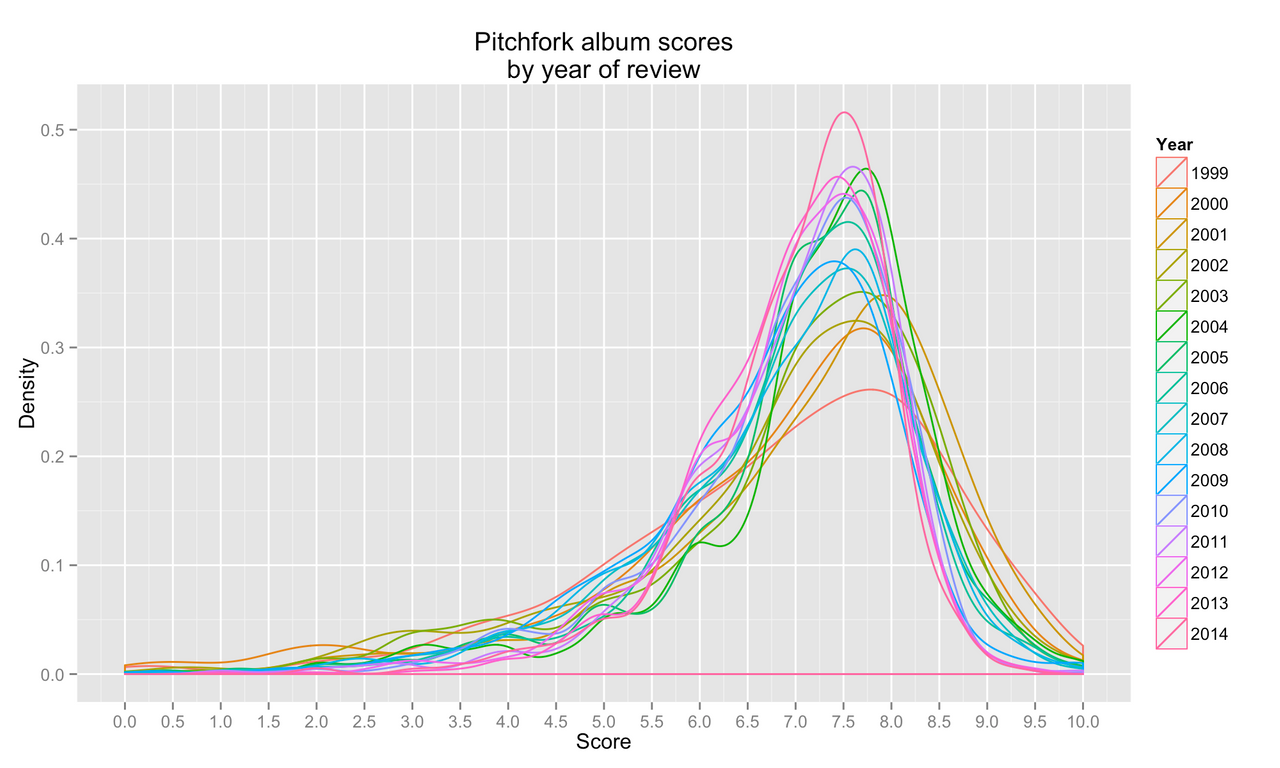

By year

Score distributions may also vary from year to year.

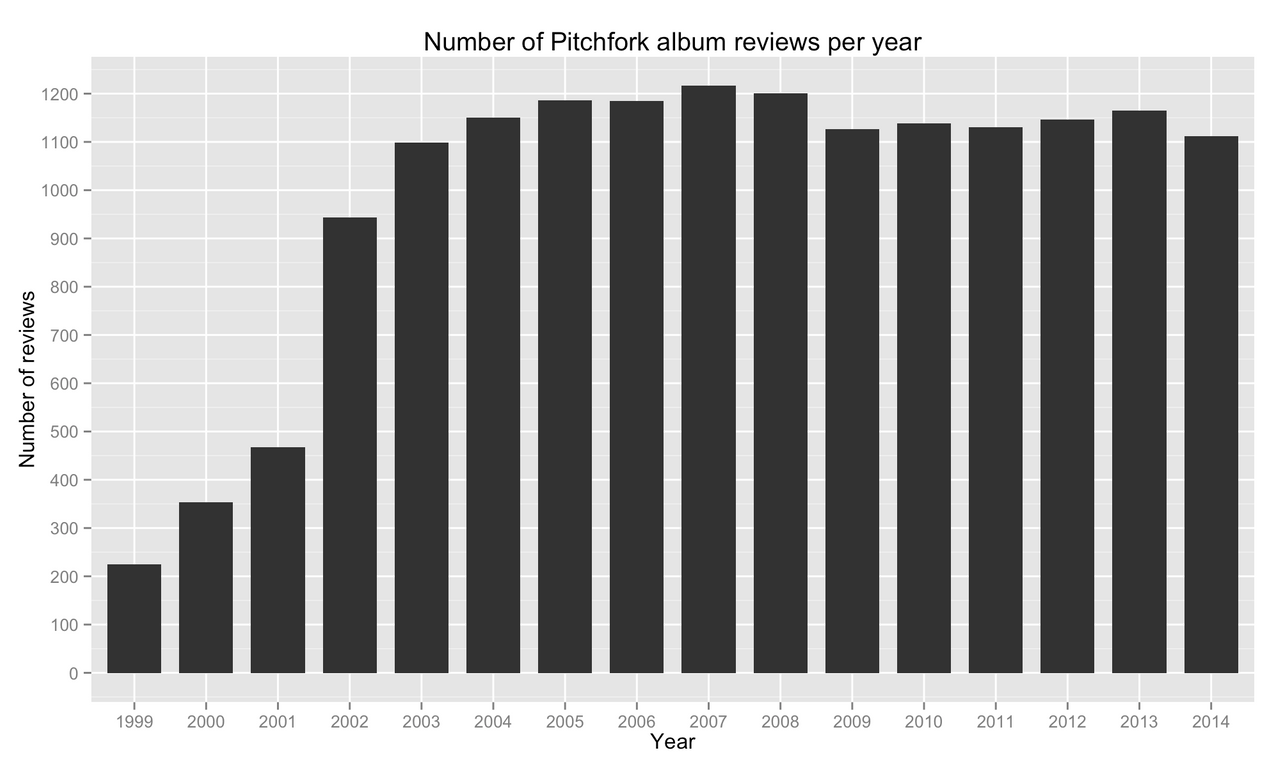

It appears the yearly score distribution has grown over time to closely mimic the overall scoring pattern above. The mildly uncharacteristic score distributions in the earlier years are likely a result of two factors. First, without a historical index of album scores to consult, Pitchfork reviewers were tasked with determining their own scoring rubrics. Second, Pitchfork reviewed fewer albums during its formative years so a higher variability in scores is to be expected.

Indeed, it appears Pitchfork did not reach a visible “steady state” of about 1,100 - 1,200 reviews per year until around 2004/2005. Note the drop in total reviews from 2008 to 2009 is a direct result of our eliminating ‘Best New Reissue’ albums from the data set. While Pitchfork has been reviewing reissues for many years, the ‘Best New Reissue’ designation was not introduced until 2009.

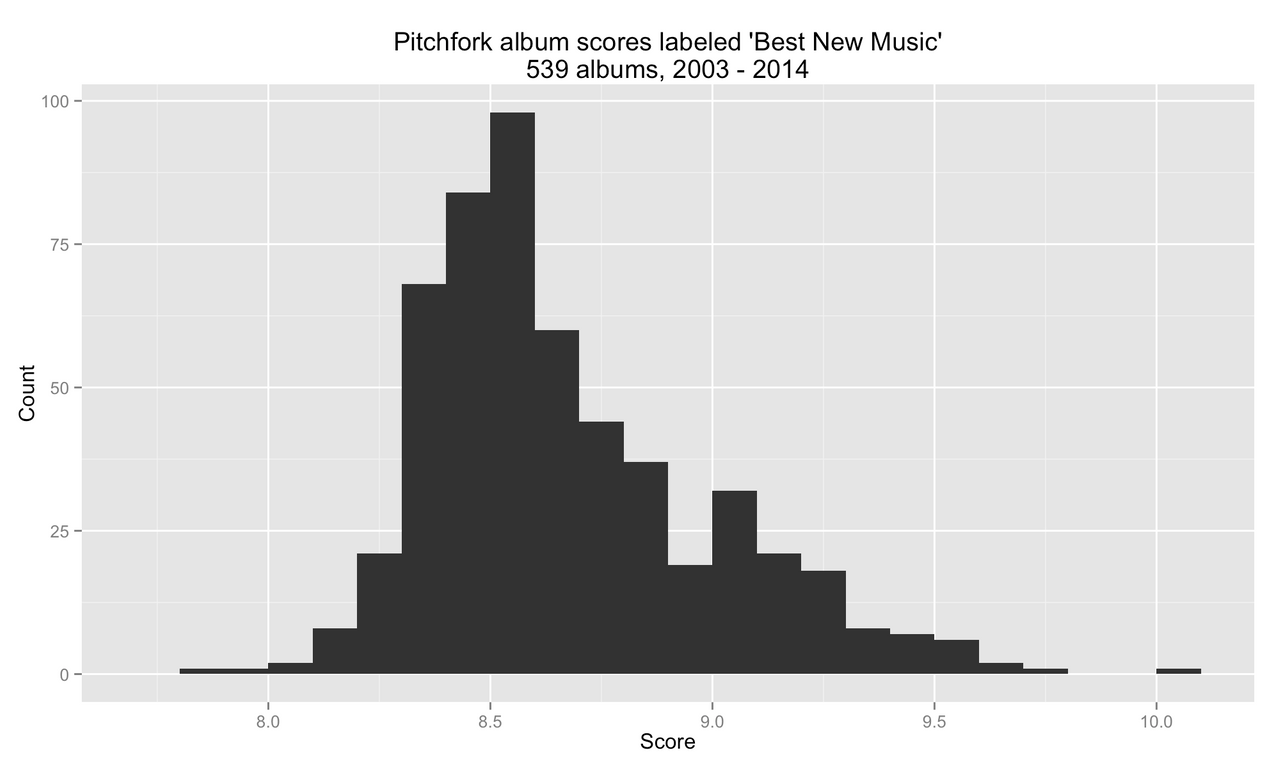

By ‘Best New Music’

In addition to the numeric score attributed to every album, Pitchfork reviewers can distinguish exceptional new releases by labeling them as ‘Best New Music’ (BNM). Since the introduction of BNM in 2003, just 539 new releases of 13,825 total albums (3.9%) have been deemed worthy of the distinction. Despite its regular use and the clear honor associated with receiving it, the BNM accolade was not formally defined until 2012 when Pitchfork responded to a reader’s question of “How does Pitchfork’s ‘Best New Music’ system work?”:

The truth of it is breathtakingly simple: Editors choose Best New Music albums based on the records that we think are the cream of the crop. These are excellent records that we feel transcend their scene and genre. When an album gets Best New Music, we think there’s a very good chance that someone who doesn’t generally follow this specific sphere of music will find a lot to enjoy in it.

Calling this definition “breathtakingly simple” is a bit of a misnomer considering its high subjectivity. Regardless, what kind of scores can we expect from BNM albums?

BNM album scores average a mean score of 8.62, median of 8.5, with standard deviation 0.324. The five most common BNM scores are 8.5, 8.4, 8.3, 8.6, 8.7. Only 2 BNM albums have scored below 8.0.

The reviewer effect

My primary interest in this analysis is the effect of reviewer on album score. Of course, without performing a controlled experiment I cannot safely conclude that “reviewer x has effect y” on the score of any given album. I am simply looking to characterize scoring patterns across a wide range of possible reviewers on the Pitchfork staff.

There are 319 total reviewers, a term I use loosely here because a very small handful of these reviews are collaborations among two or more reviewers. How many reviews have each of these reviewers contributed?

## Min. 1st Qu. Median Mean 3rd Qu. Max.

## 1.00 3.00 13.00 53.53 48.00 805.00

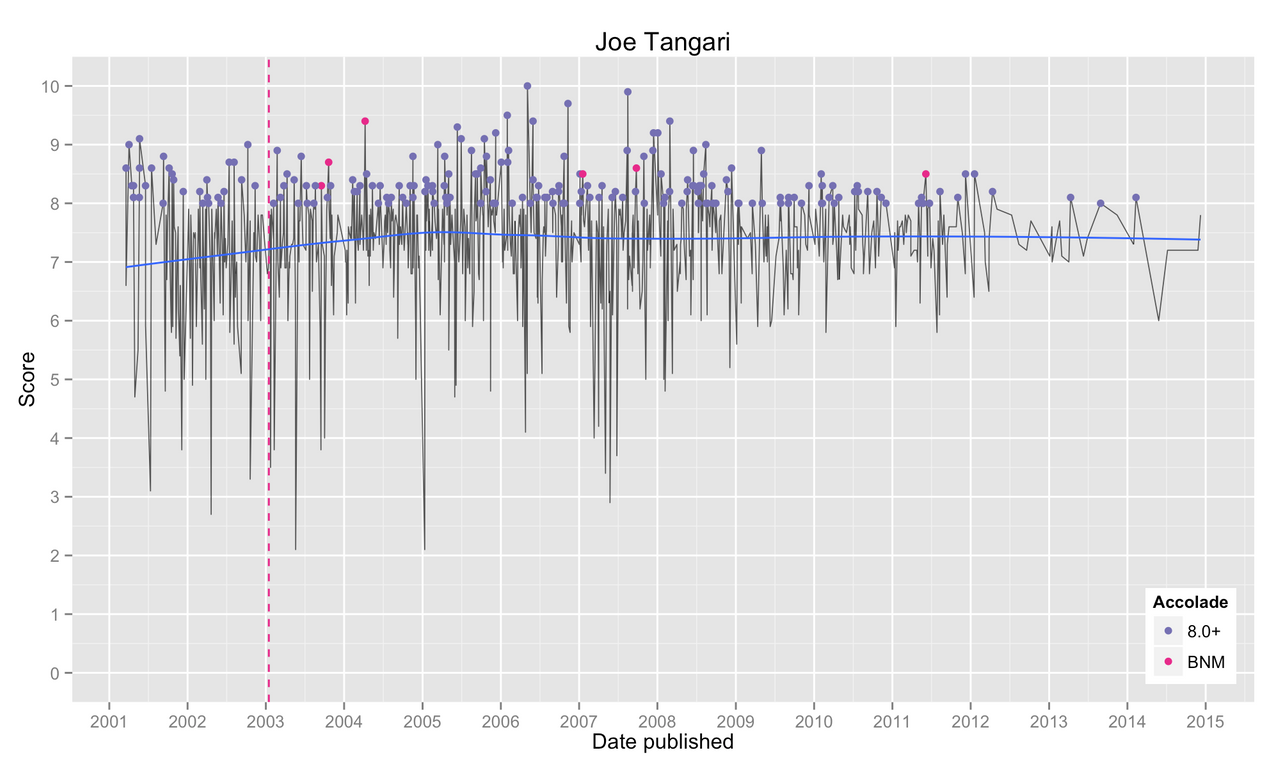

Half of all reviewers have contributed 13 or fewer reviews while the 25% most prolific reviewers have contributed 48 or more reviews. There are 74 reviewers with at least 50 reviews and 45 reviewers with at least 100 reviews. Leading the pack is Joe Tangari with a whopping 805 reviews. Go Joe!

We must ensure our analysis is not adversely influenced by reviewers for which we have insufficient data. Thus, for the sake of the following analyses, we will restrict our attention to only those reviewers with 100 or more reviews. These 45 reviewers account for a staggering 70.21% of all reviews on Pitchfork.

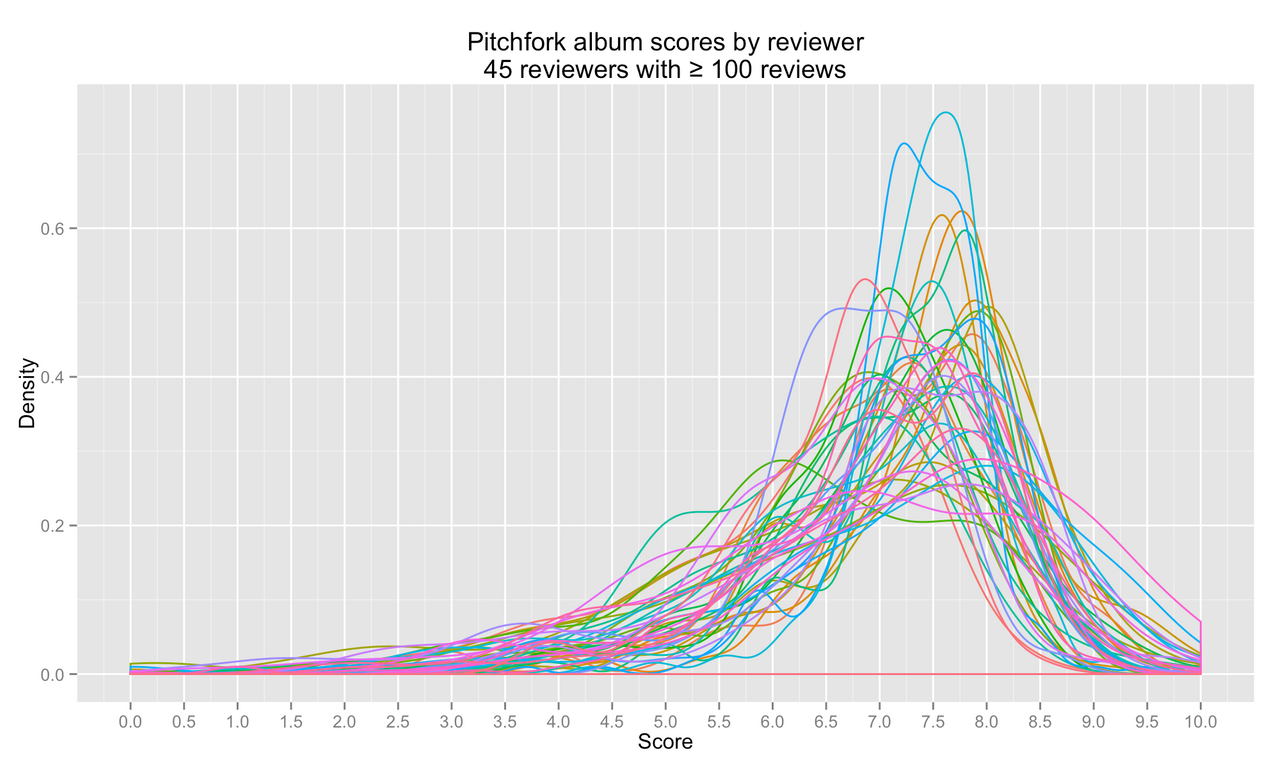

How does score distribution vary from reviewer to reviewer?

Yikes! There is a surprising lack of continuity in score distribution from reviewer to reviewer. Some reviewers assign scores very frequently around 7.0, 7.5, or 8.0. Other reviewers are much more variable in their scores. We even identify a handful of bimodal distributions in the bunch, suggesting some reviewers have go-to scores to rate good and bad albums.

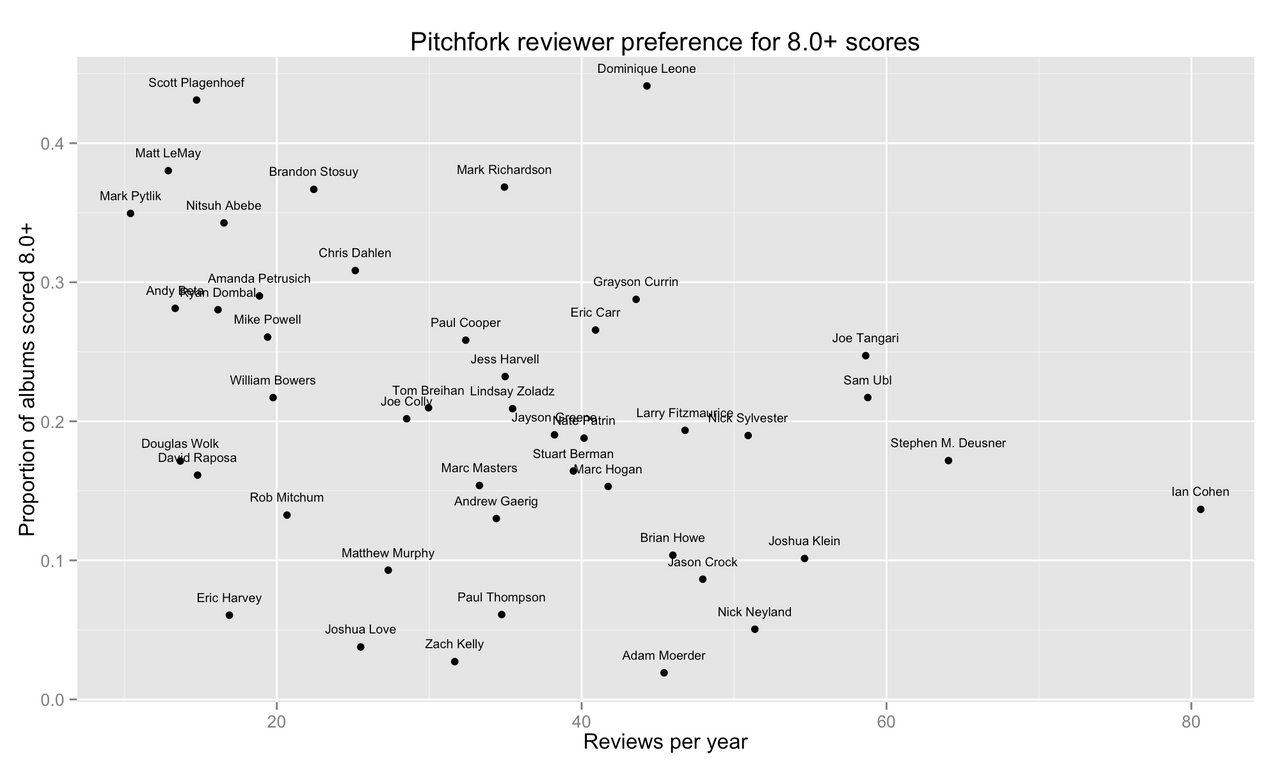

By 8.0+

Pitchfork defines high-scoring albums as those receiving scores of 8.0 or greater (8.0+) by their respective reviewer. High-scoring albums get special attention, so a score of 8.0 is much more valuable than a 7.9. We therefore investigate differences in reviewer preference for assigning high scores. For each reviewer with at least 100 published reviews, we plot their proportion of 8.0+ album scores against their approximate number of album reviews published per year, a measure of their activity as a reviewer.

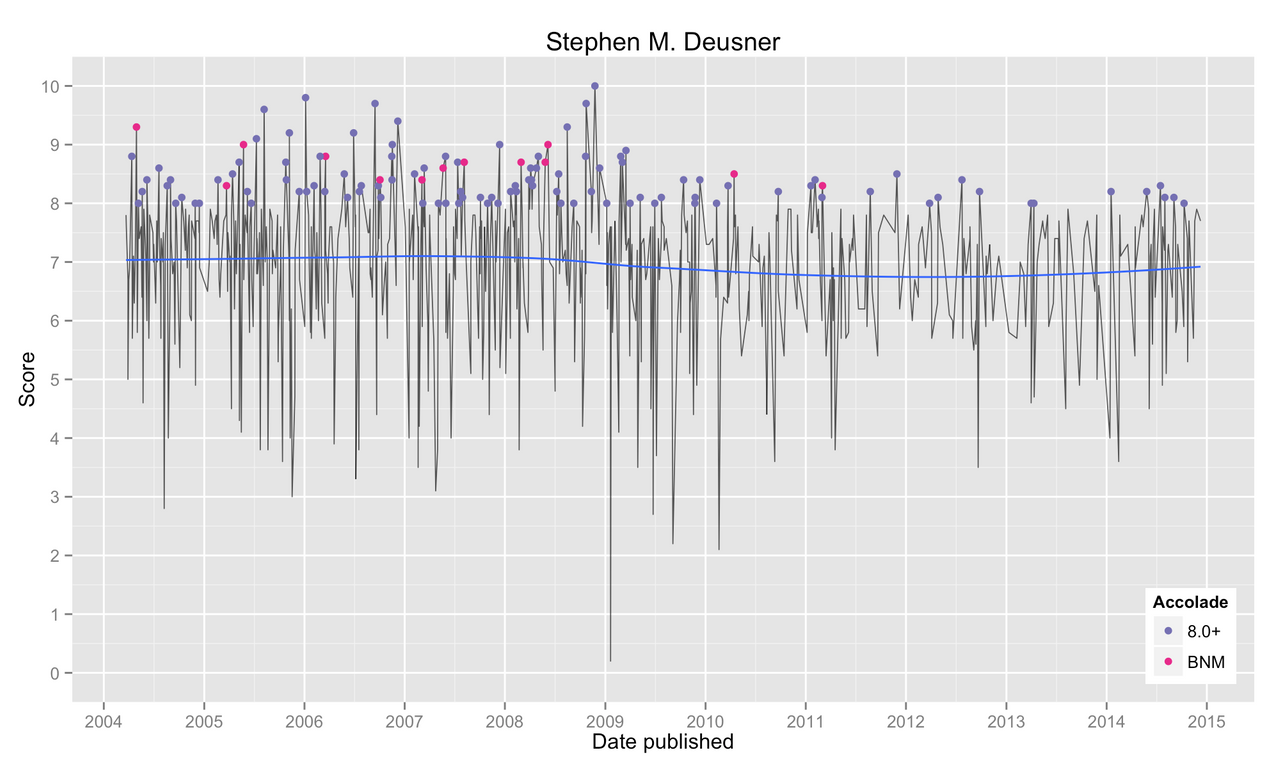

Ian Cohen wins the award for most active reviewer with over 80 reviews per year on average, 13.7% of which regularly receive an 8.0+. After Cohen, the next most active reviewers are Stephen M. Deusner (with 17.2% of his album reviews earning 8.0+), Sam Ubl (21.7%), and Pitchfork’s most prolific reviewer Joe Tangari (24.7%).

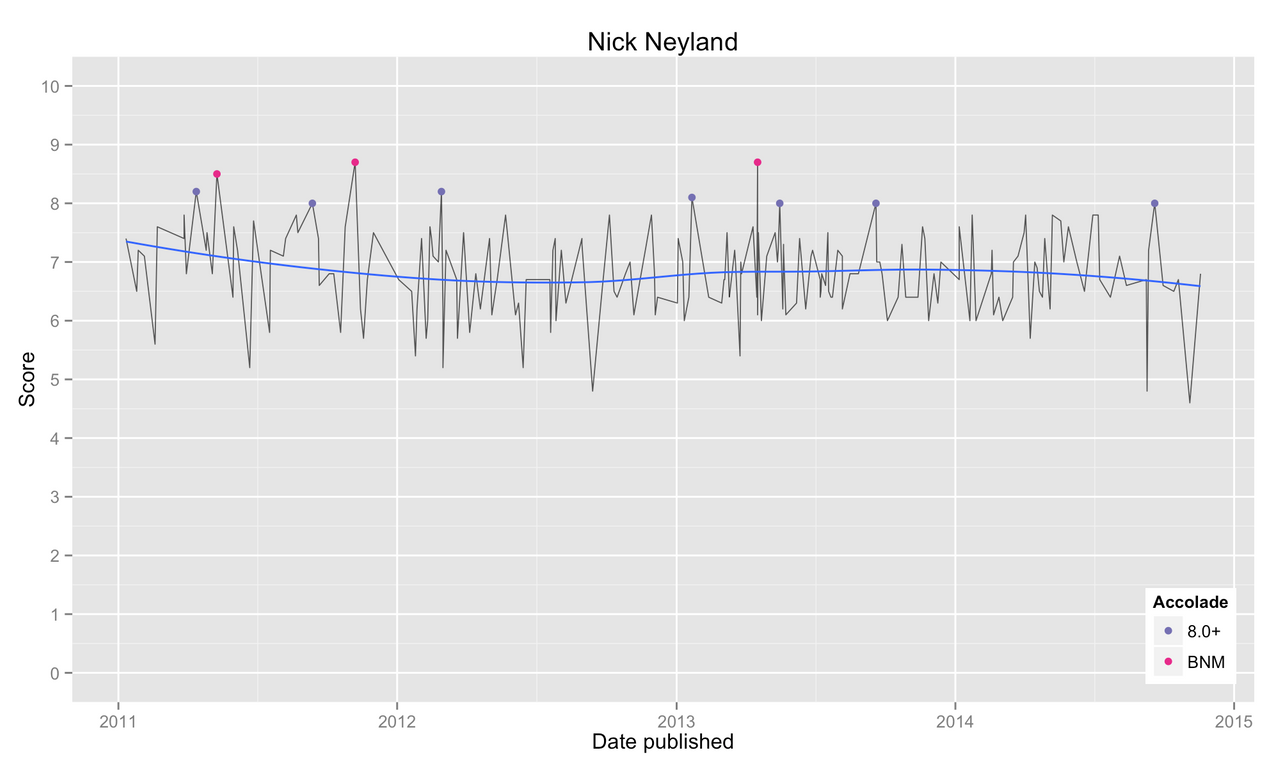

Some reviewers are very conservative with assigning high scores, such as Nick Neyland (5.1%), Joshua Love (3.8), and Zach Kelly (2.7%). Adam Moerder is notoriously difficult to please; a paltry 1.9% of albums he has reviewed have earned an 8.0+ despite his reviewing an average of 45.41 albums per year.

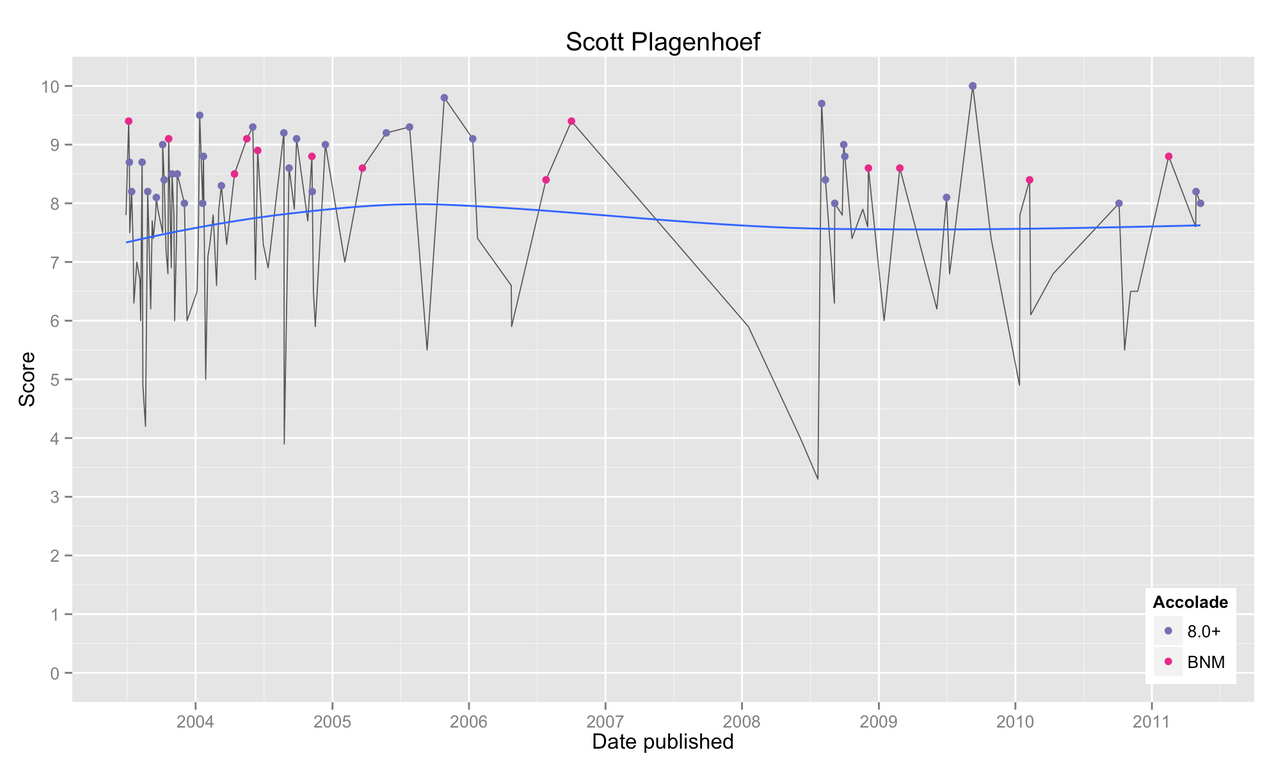

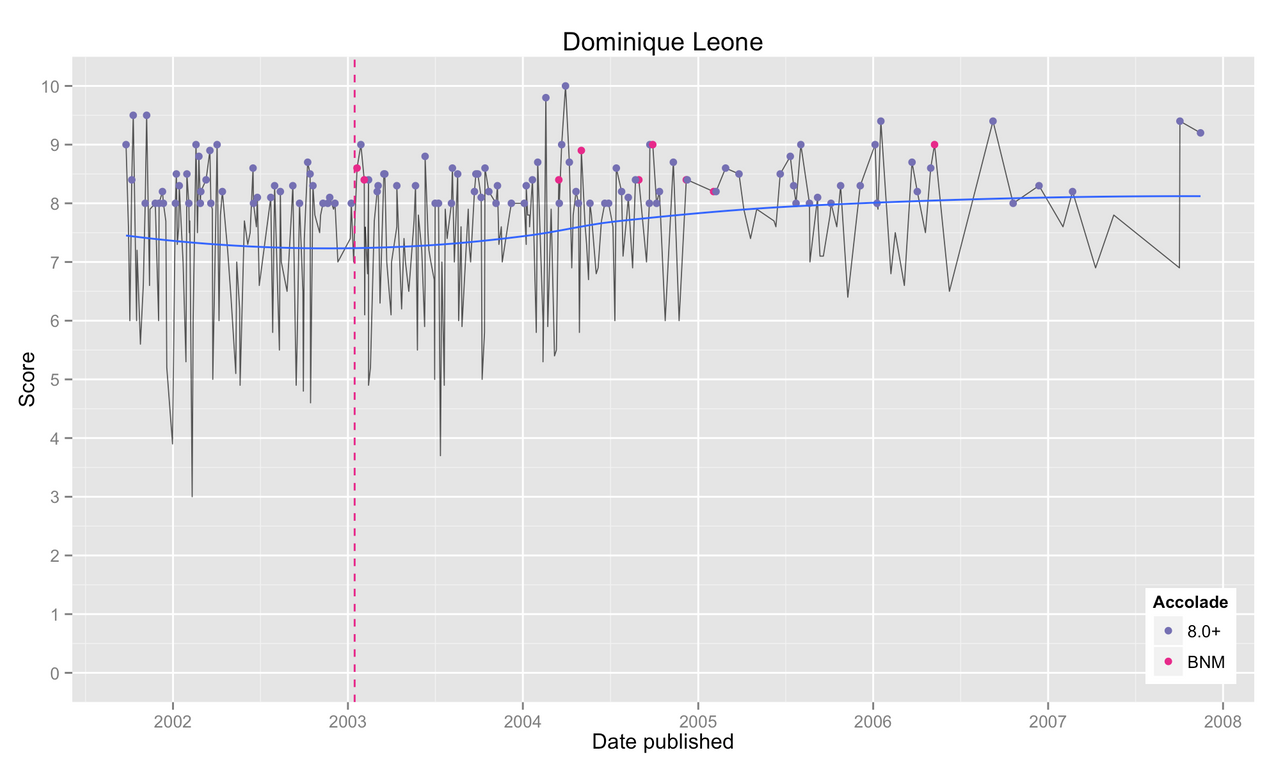

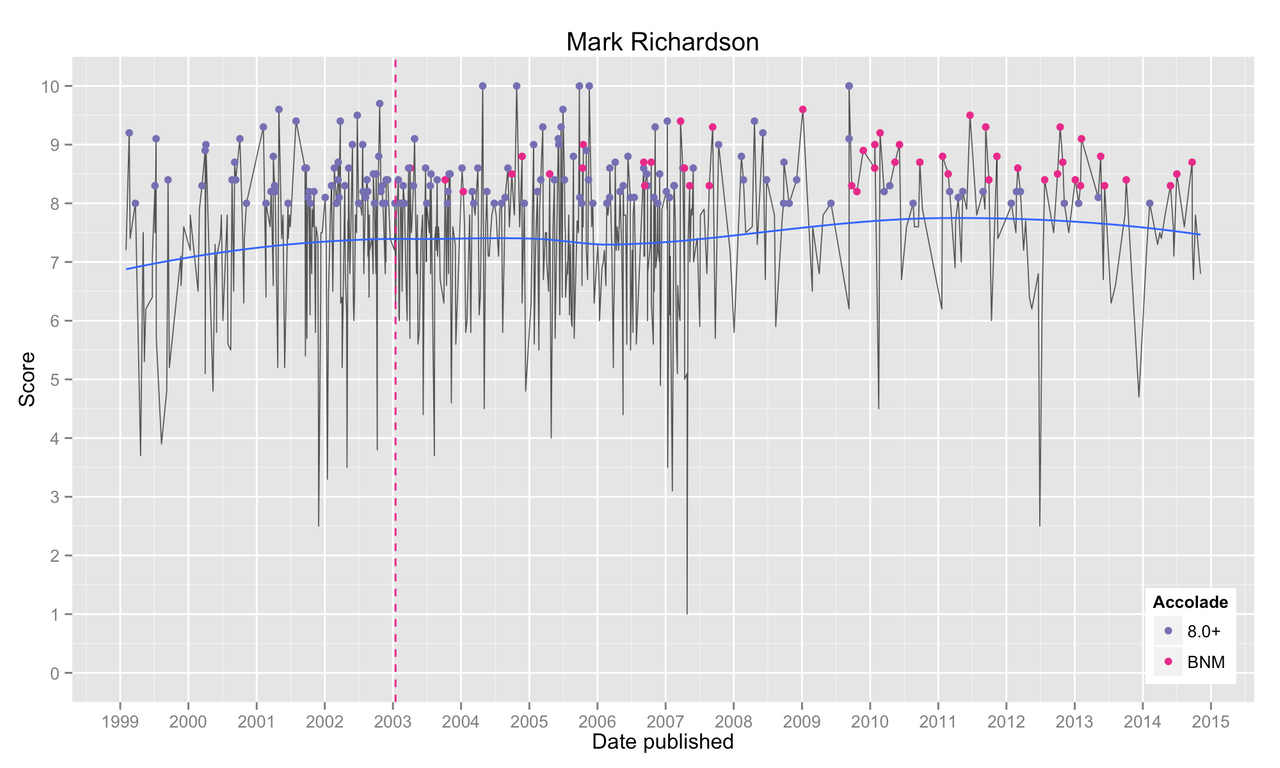

On the liberal end of the spectrum, Dominique Leone publishes 44.28 reviews per year, a rate very close to Moerder’s, but 44.1% of albums he reviews earn a prestigious 8.0+. Scott Plagenhoef is similarly liberal at 43.1%, though he is not quite so active. Other liberal reviewers include Matt LeMay (38%), Mark Richardson (36.8%), and Brandon Stosuy (36.7%).

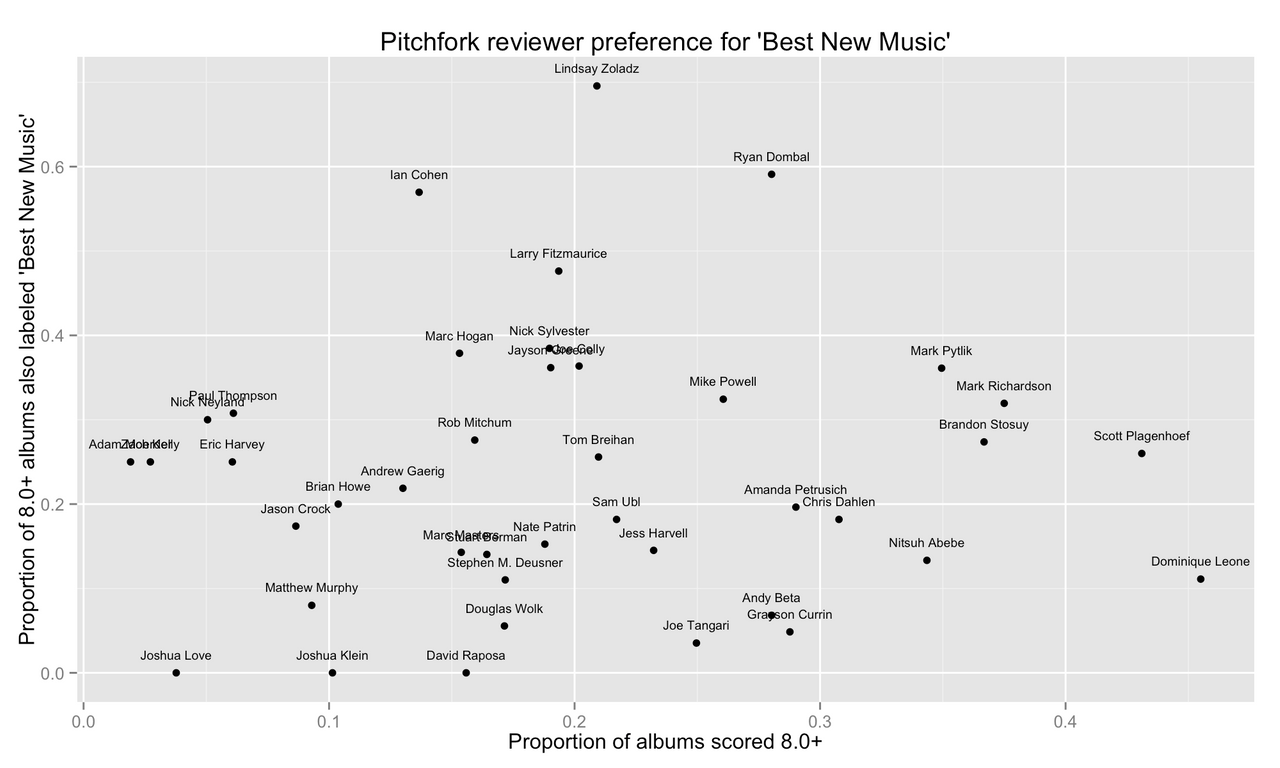

By ‘Best New Music’

Now, high scores are great, but BNM albums get extra special attention, particularly from rabid music aficionados like myself. Only albums scored 8.0+ are considered for BNM by their reviewer (with very few exceptions). But how drastically do reviewers differ in awarding their 8.0+ albums a head-turning ‘Best New Music’ accolade? Because BNM was not introduced by Pitchfork until 2003, we restrict ourselves to the 13825 album reviews published in 2003 or later.

Ian Cohen, Pitchfork’s most active reviewer, awards BNM to a high 57% of his 8.0+ reviews. The other active reviewers are considerably less generous: Stephen M. Deusner (11%), Sam Ubl (18.2%) and Joe Tangari at a miniscule 3.5%.

Reviewers noted for commonly assigning high scores tend to be relatively moderate with further awarding BNM to their 8.0+ albums. This includes Mark Richardson (31.9%), Brandon Stosuy (27.4%), and Scott Plagenhoef (26%). A notable exception is Dominique Leone. Despite having the highest proportion of 8.0+ reviews, he awards BNM to a rather low 11.1% of these albums.

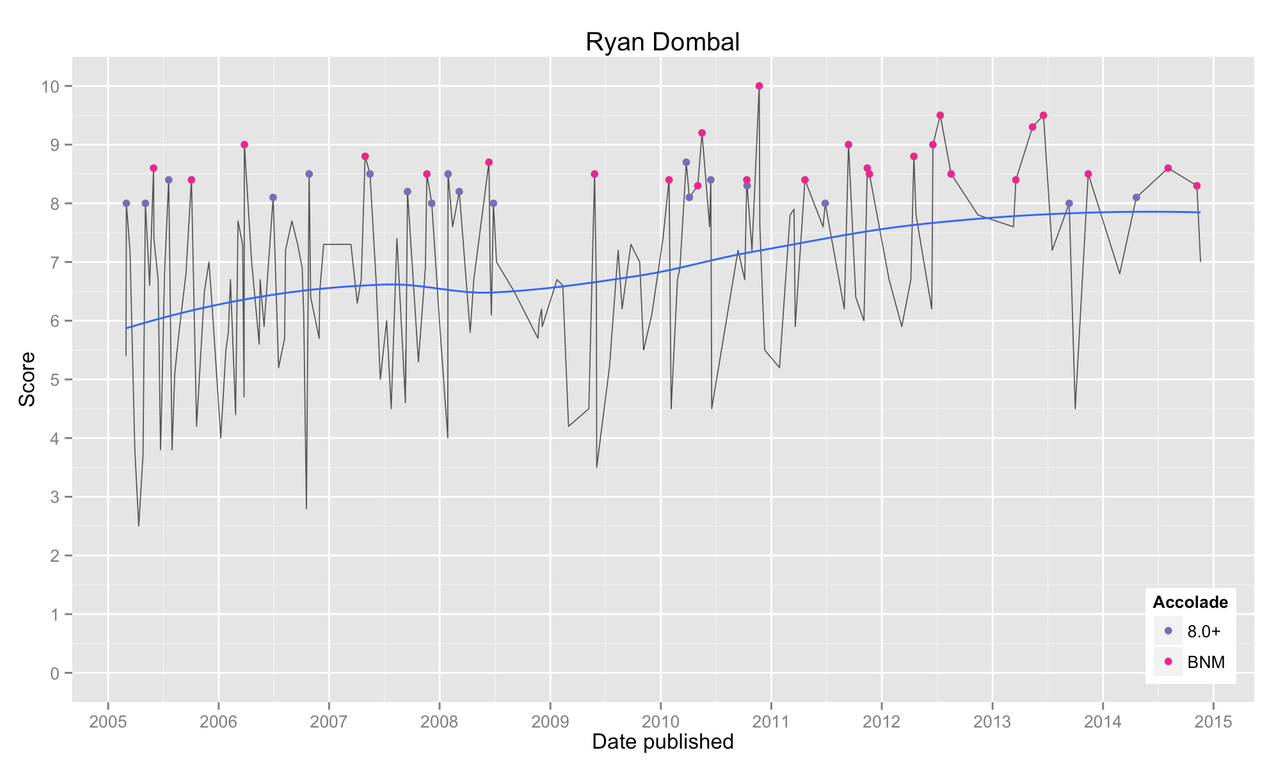

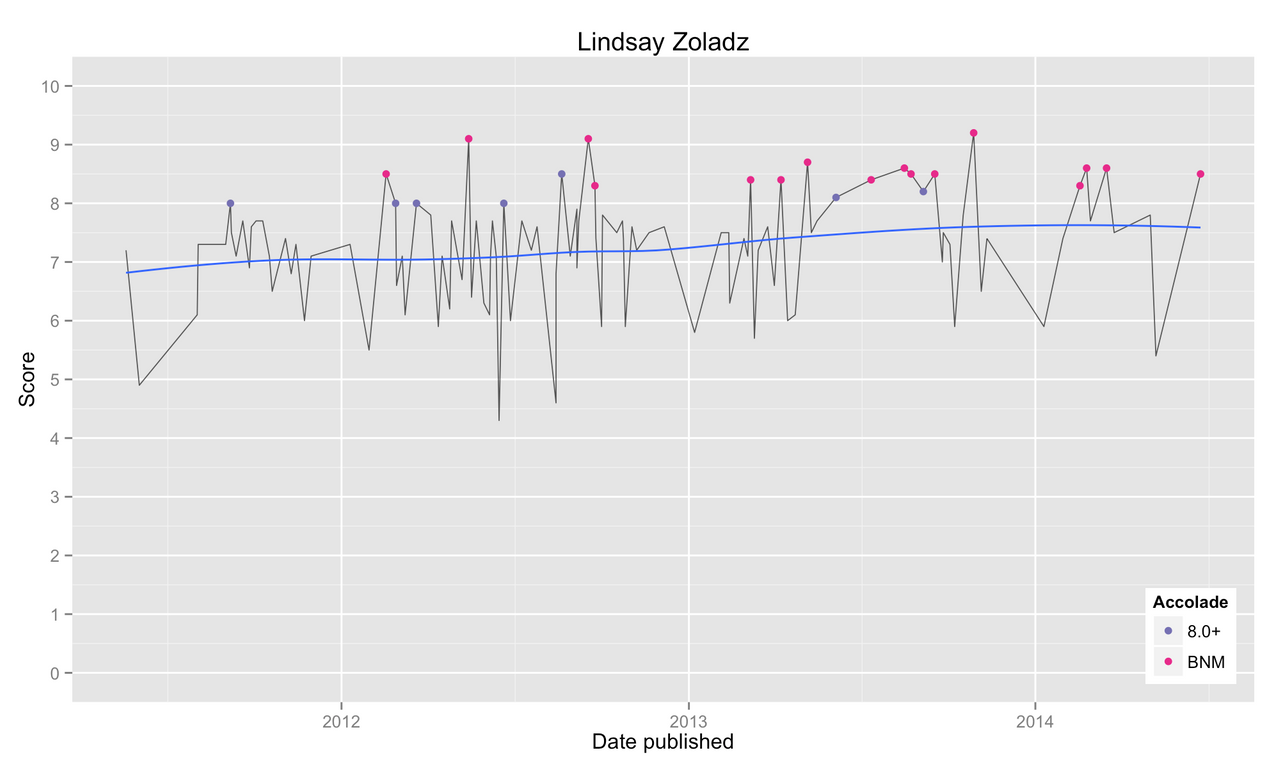

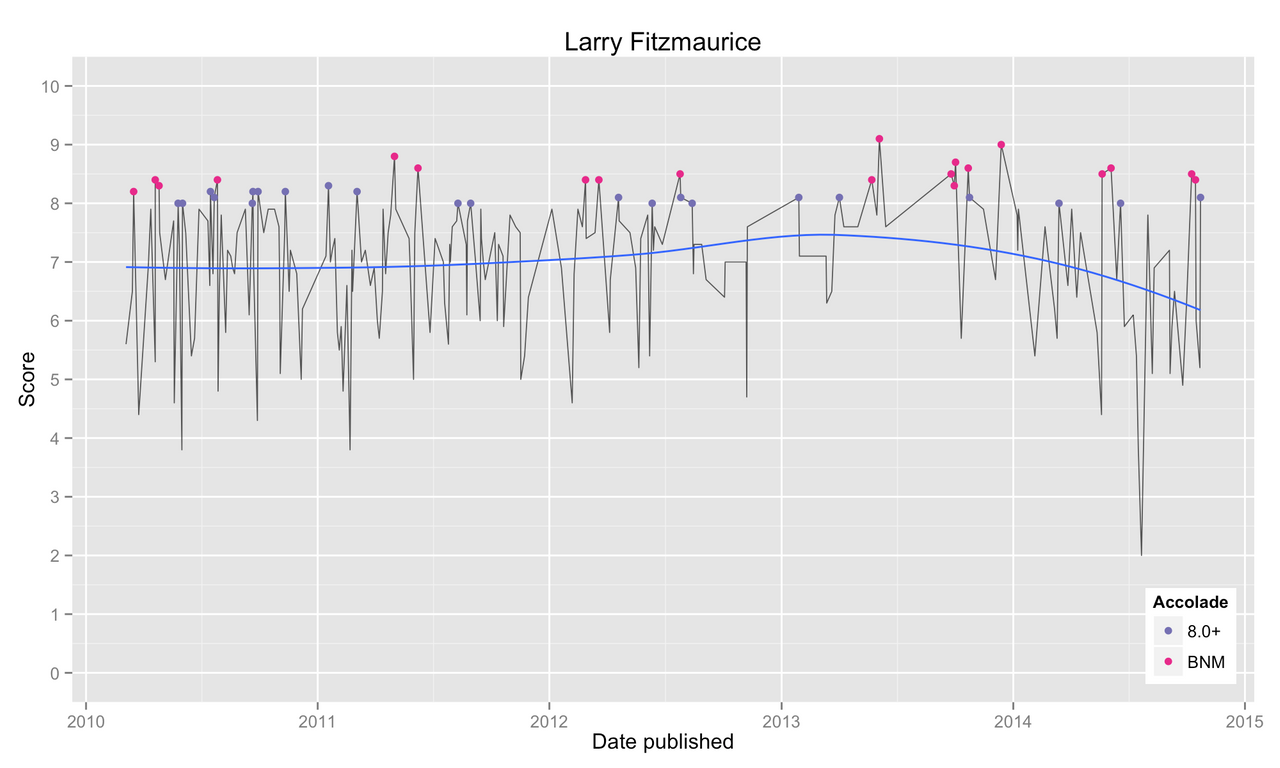

By comparison, some reviewers can’t seem to get enough BNM! Lindsay Zoladz awards BNM to a staggering 69.6% of her 8.0+ scores. Ryan Dumbai has a slightly lower BNM percentage (59.1%) but he is also more likely to assign a high score to the albums he reviews. Also of note is Larry Fitzmaurice at 47.6%.

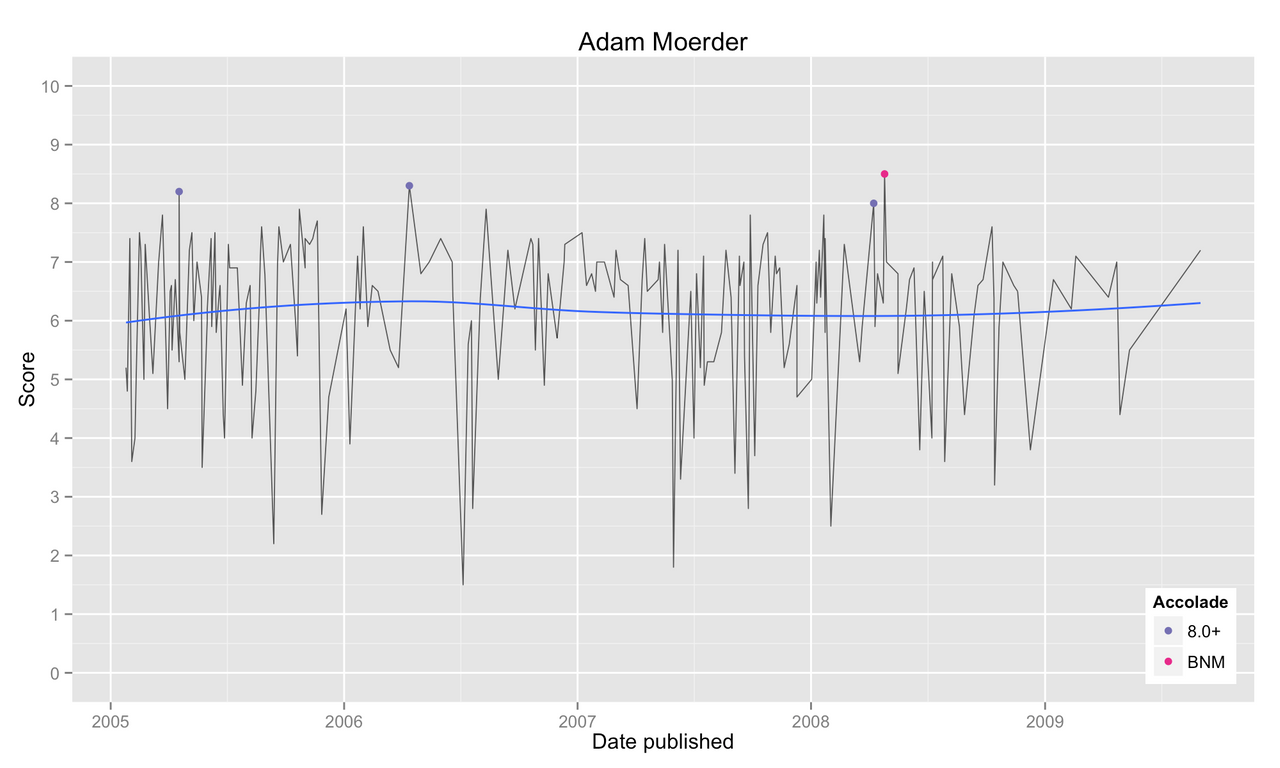

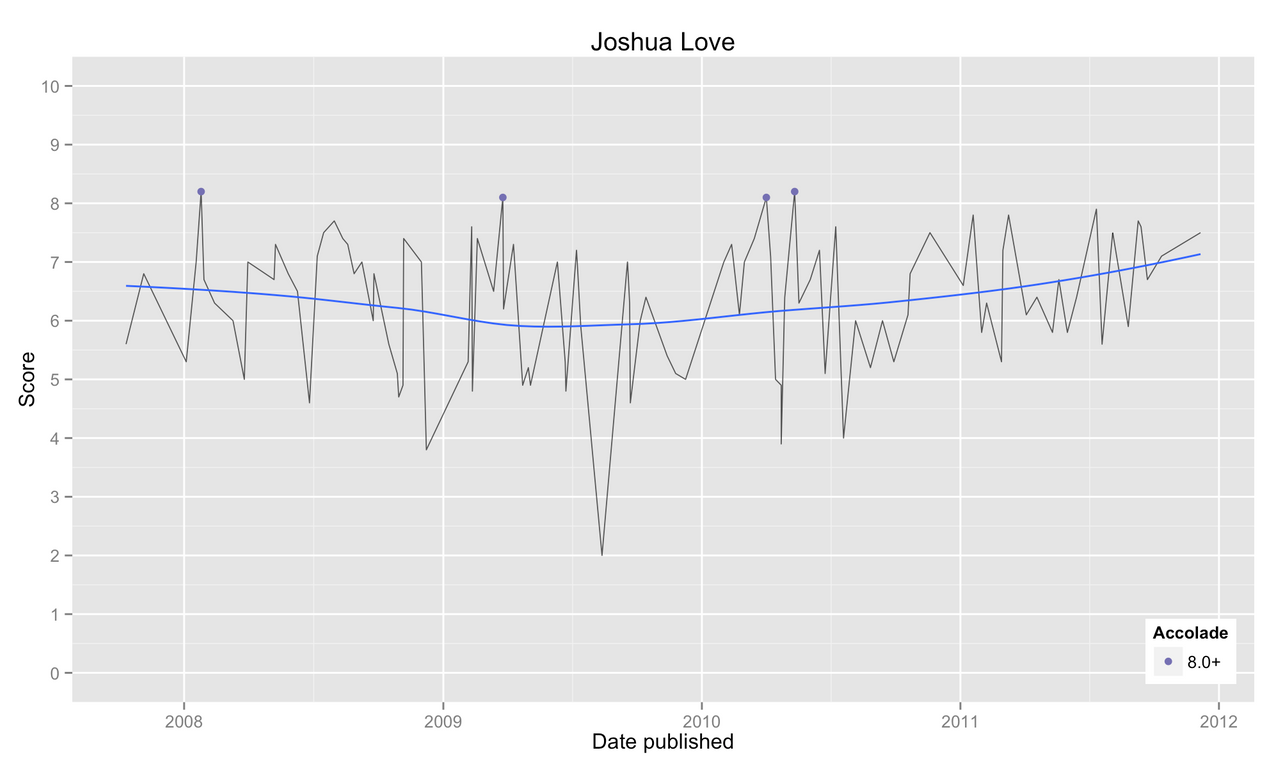

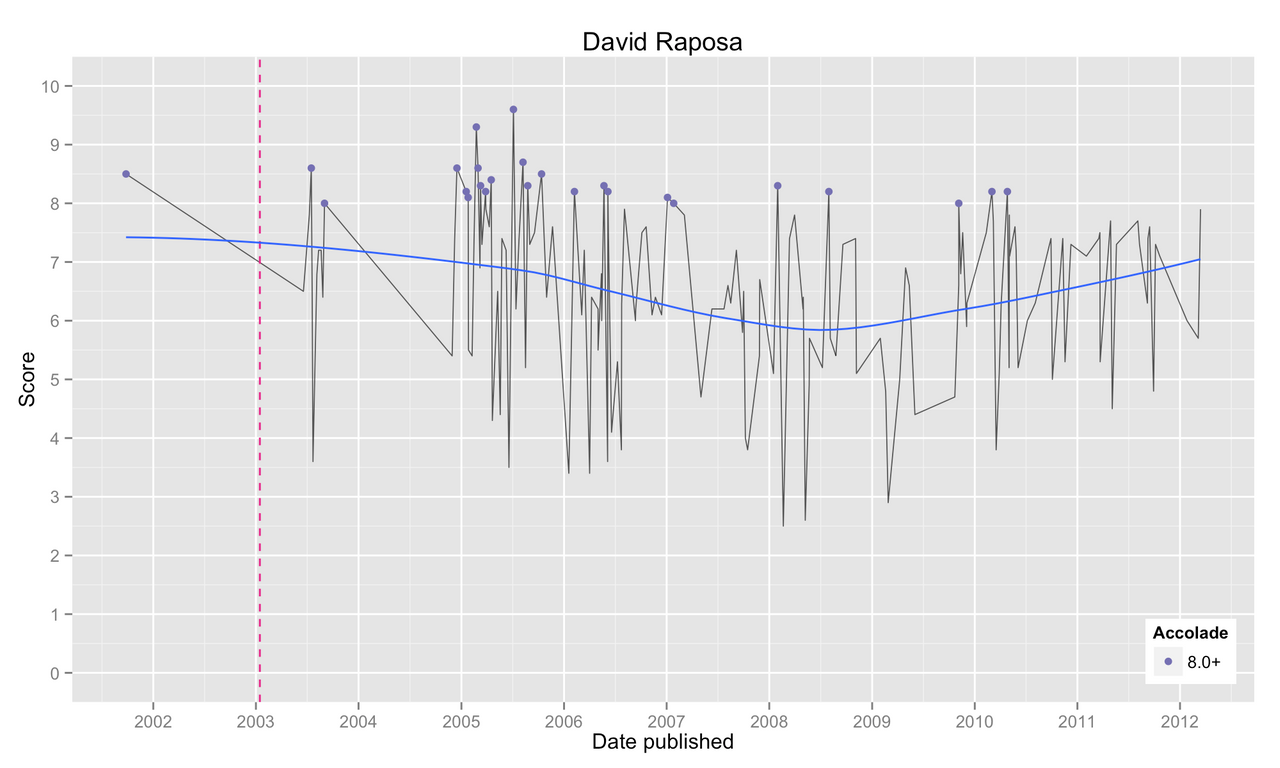

Conservative reviewers, those reluctant to assign high scores to their album reviews, range from drastically low to moderate in their use of BNM. Higher variability is to be expected here as the strict scoring habits of these reviewers allow very few albums to be eligible for BNM. That being said, Nick Neyland awards BNM to 30% of his 8.0+ album reviews, Zach Kelly (25%) and Adam Moerder (25%). In his history of 106 published album reviews, Joshua Love has never once labeled an album as BNM. Love is not alone; Joshua Klein and David Raposa have also never awarded BNM in their respective 217 and 155 published reviews.

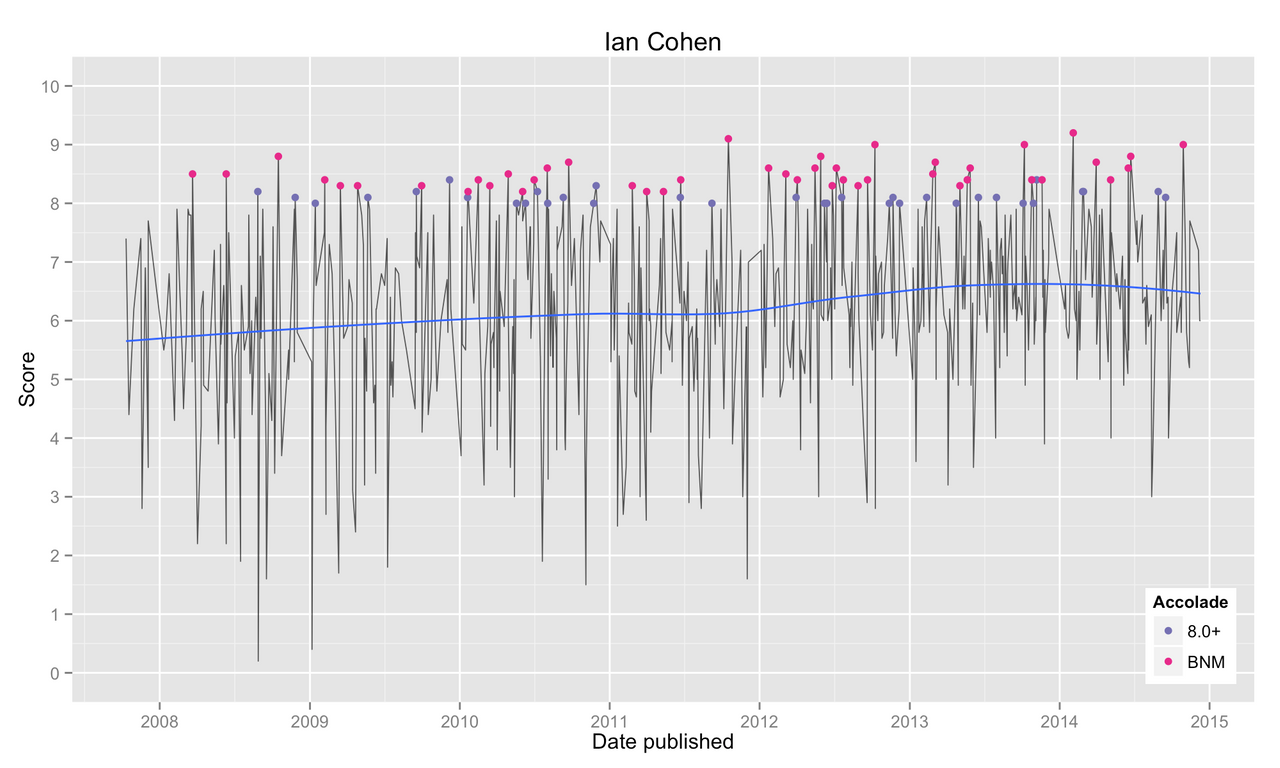

By date published

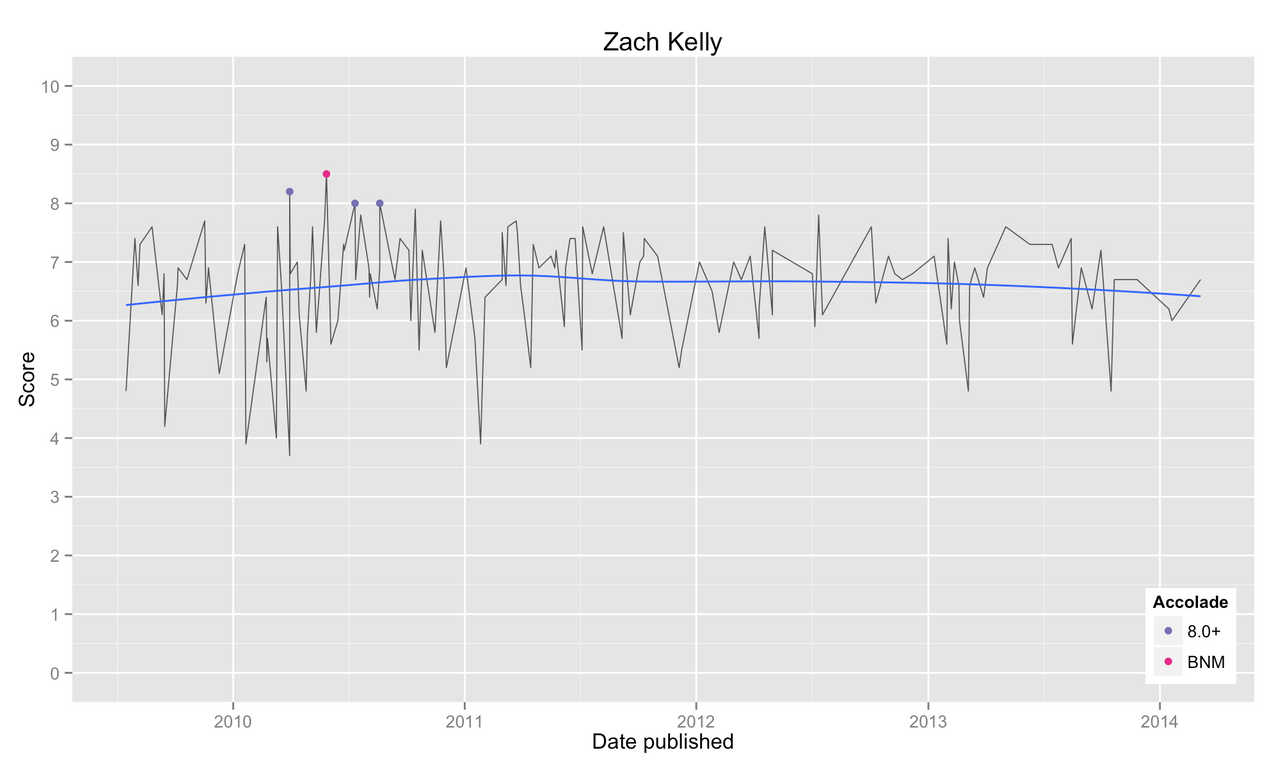

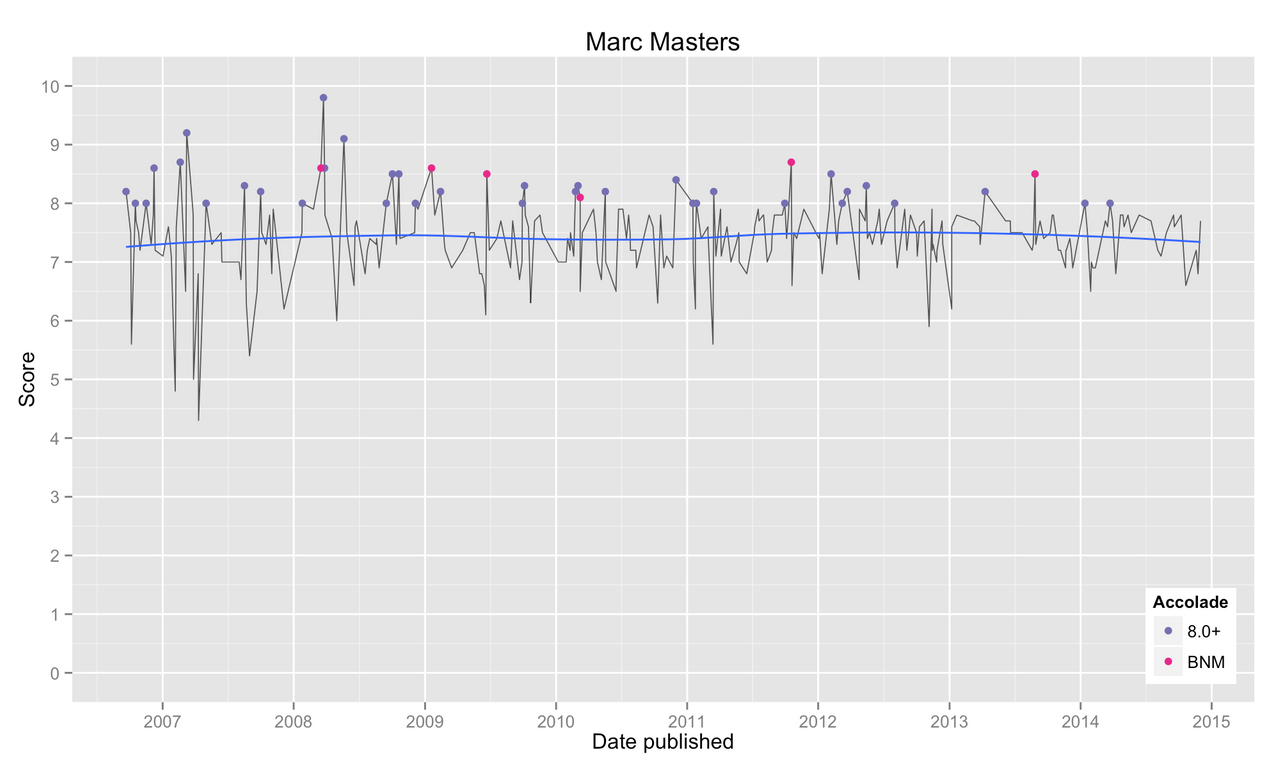

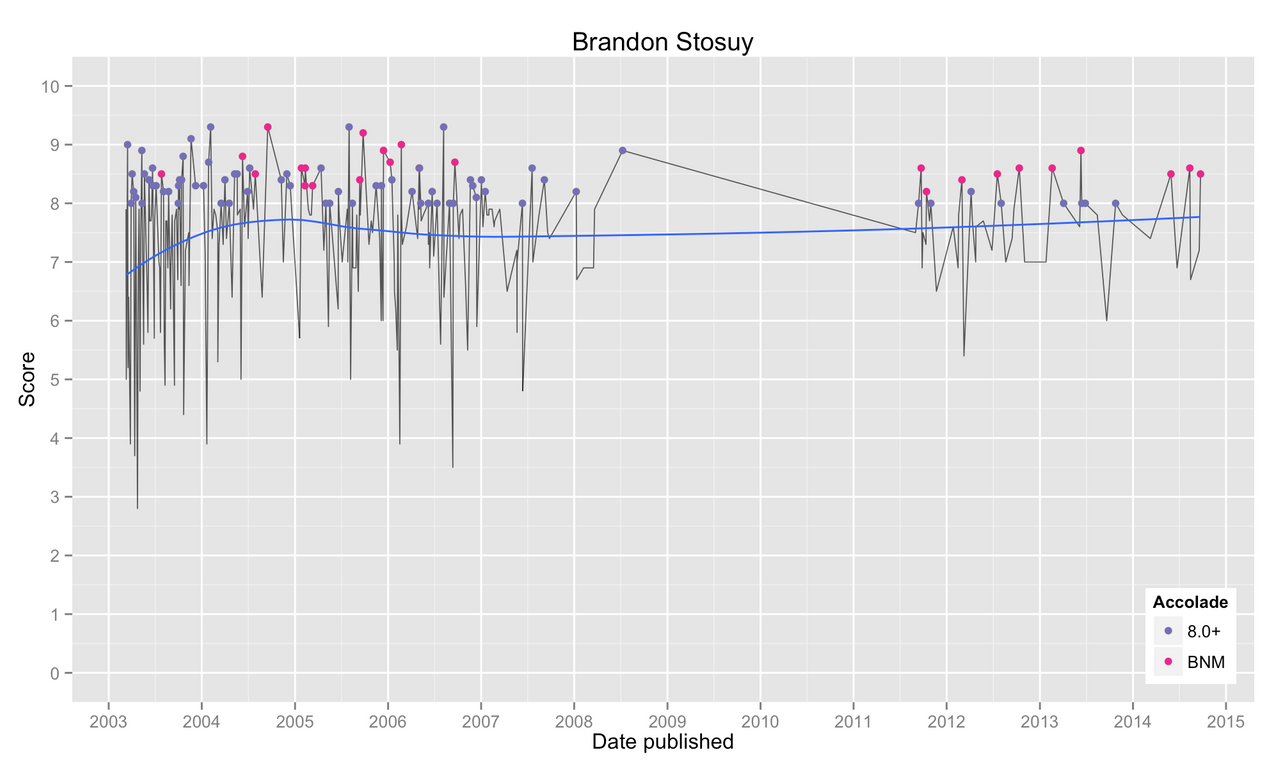

Perhaps the best way to visualize reviewer behavior is to plot a reviewer’s scoring history over time. Each plot includes the following information:

Scores over time

A line graph in grey illustrates a reviewer’s scoring history from their first published Pitchfork album review to their most recent. We see a high variability in scores assigned by Pitchfork’s most active reviewers, owing presumably to the high frequency of albums that hit their desk for review.

This stands in stark contrast to reviewers like Nick Neyland, Zach Kelly, and Marc Masters who, while less active, show very low variance in the scores they assign.

Average score over time

A LOESS smoother in blue approximates a reviewer’s average score over time. Most reviewers consistently average around 7.0 or 6.5. Reviewers identified as liberal with high scores show averages that hover closer to 8.0.

Conservative reviewers, including Ian Cohen above, attain averages as low as 6.0.

8.0+ and ‘Best New Music’

Colored points identify album reviews earning 8.0+ (purple) and BNM (pink), an accolade that did not exist prior to 2003. A vertical dotted line (pink) in some plots marks BNM’s first recorded use on January 15, 2003. Some reviewers exhibit a strong tendency to assign high scores to the albums they review.

Meanwhile, other reviewers are slightly more reluctant to assign high scores, but when they do they often further distinguish the album as BNM.

Discussion

I do not pretend to know how Pitchfork reviewers come to be responsible for reviewing particular albums. Are they randomly assigned? I highly doubt it, this seems way too inefficient as you will end up assigning, say, a death metal album to a reviewer who is better versed in the nuances of lo-fi folk music. Perhaps reviewers choose for themselves which albums to review? While more plausible, this system is not without its flaws. For example, who bears the responsibility for albums nobody has selected for review? Maybe it’s simply a mish-mash of anything and everything. Sometimes the reviewer selects a specific album to review. Other times they are asked to review something wildly off their radar.

Whatever the process, it seems likely that every staff member at Pitchfork sees albums from all walks of the music world: groundbreaking new music, atrocious flops, and all shades inbetween. However, despite relative uniformity in aggregate album quality from reviewer to reviewer, the members of the Pitchfork staff differ drastically in their reviewing behaviors. Where some reviewers assign high and low scores with impunity, others seldom venture beyond a comfortable 6.0 - 8.0 range. Certain reviewers have reviewed hundreds of albums without once acknowledging a single album as ‘Best New Music,’ while others appear to assign high scores and BNM like they’re going out of style.

In the absence of a well-defined scoring system, Pitchfork reviewers have developed their own personal rubrics for judging new music. Now, this might be innocuous if not for phenomena like the Pitchfork Effect. An album that reaches Mark Richardson’s desk, say, likely has a much better shot at high praise than if that same album hit Adam Moerder’s desk. With fame and fortune hanging in the balance, Pitchfork’s willful neglect of acknowledging reviewer variability seems irresponsible at best.

A solution to this may be to allow multiple reviews per album. That is, why not allow three members to review an album and assign it the average of their scores? This is not the cheapest option for Pitchfork, surely, but an average of three scores is resistant to the whims of an individual reviewer and ought to better capture the musical novelty of a newly released album. For a website that thrives on controversy, however, I would not hold my breath.

I am not the first person to attempt an analysis of Pitchfork album reviews. In recent years, Johnny Stoddard identified the top-rated artists and albums of 2000 - 2010, Alex Pounds attempts (but doesn’t complete) an investigation of the relationship between an artist’s Pitchfork popularity and their number of listeners, and Jim Duke summarized album scores overall, over time, and, very briefly, by reviewer using data obtained by Christopher Marriott’s Pitchfork web scraper. ↩